Physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

is a branch of

science

Science is a systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe.

Science may be as old as the human species, and some of the earliest archeological evidence for ...

whose primary objects of study are

matter

In classical physics and general chemistry, matter is any substance that has mass and takes up space by having volume. All everyday objects that can be touched are ultimately composed of atoms, which are made up of interacting subatomic partic ...

and

energy

In physics, energy (from Ancient Greek: ἐνέργεια, ''enérgeia'', “activity”) is the quantitative property that is transferred to a body or to a physical system, recognizable in the performance of work and in the form of heat a ...

. Discoveries of physics find applications throughout the

natural science

Natural science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer review and repeatab ...

s and in

technology

Technology is the application of knowledge to reach practical goals in a specifiable and reproducible way. The word ''technology'' may also mean the product of such an endeavor. The use of technology is widely prevalent in medicine, science, ...

. Physics today may be divided loosely into

classical physics

Classical physics is a group of physics theories that predate modern, more complete, or more widely applicable theories. If a currently accepted theory is considered to be modern, and its introduction represented a major paradigm shift, then the ...

and

modern physics

Modern physics is a branch of physics that developed in the early 20th century and onward or branches greatly influenced by early 20th century physics. Notable branches of modern physics include quantum mechanics, special relativity and general ...

.

Ancient history

Elements of what became physics were drawn primarily from the fields of

astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

,

optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultraviole ...

, and

mechanics

Mechanics (from Ancient Greek: μηχανική, ''mēkhanikḗ'', "of machines") is the area of mathematics and physics concerned with the relationships between force, matter, and motion among physical objects. Forces applied to objects r ...

, which were methodologically united through the study of

geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

. These mathematical disciplines began in

antiquity with the

Babylonia

Babylonia (; Akkadian: , ''māt Akkadī'') was an ancient Akkadian-speaking state and cultural area based in the city of Babylon in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq and parts of Syria). It emerged as an Amorite-ruled state c. ...

ns and with

Hellenistic

In Classical antiquity, the Hellenistic period covers the time in Mediterranean history after Classical Greece, between the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC and the emergence of the Roman Empire, as signified by the Battle of Actium in ...

writers such as

Archimedes

Archimedes of Syracuse (;; ) was a Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse in Sicily. Although few details of his life are known, he is regarded as one of the leading scientists ...

and

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

.

Ancient philosophy

This page lists some links to ancient philosophy, namely philosophical thought extending as far as early post-classical history ().

Overview

Genuine philosophical thought, depending upon original individual insights, arose in many cultures ...

, meanwhile, included what was called "

Physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which r ...

".

''Greek concept''

The move towards a rational understanding of nature began at least since the

Archaic period in Greece (650–480

BCE

Common Era (CE) and Before the Common Era (BCE) are year notations for the Gregorian calendar (and its predecessor, the Julian calendar), the world's most widely used calendar era. Common Era and Before the Common Era are alternatives to the or ...

) with the

Pre-Socratic philosophers

Pre-Socratic philosophy, also known as early Greek philosophy, is ancient Greek philosophy before Socrates. Pre-Socratic philosophers were mostly interested in cosmology, the beginning and the substance of the universe, but the inquiries of the ...

. The philosopher

Thales of Miletus

Thales of Miletus ( ; grc-gre, Θαλῆς; ) was a Greek mathematician, astronomer, statesman, and pre-Socratic philosopher from Miletus in Ionia, Asia Minor. He was one of the Seven Sages of Greece. Many, most notably Aristotle, regarded him ...

(7th and 6th centuries BCE), dubbed "the Father of Science" for refusing to accept various supernatural, religious or mythological explanations for natural

phenomena

A phenomenon ( : phenomena) is an observable event. The term came into its modern philosophical usage through Immanuel Kant, who contrasted it with the noumenon, which ''cannot'' be directly observed. Kant was heavily influenced by Gottfried W ...

, proclaimed that every event had a natural cause. Thales also made advancements in 580 BCE by suggesting that water is

the basic element, experimenting with the attraction between

magnet

A magnet is a material or object that produces a magnetic field. This magnetic field is invisible but is responsible for the most notable property of a magnet: a force that pulls on other ferromagnetic materials, such as iron, steel, nickel, ...

s and rubbed

amber

Amber is fossilized tree resin that has been appreciated for its color and natural beauty since Neolithic times. Much valued from antiquity to the present as a gemstone, amber is made into a variety of decorative objects."Amber" (2004). In Ma ...

and formulating the first recorded

cosmologies.

Anaximander

Anaximander (; grc-gre, Ἀναξίμανδρος ''Anaximandros''; ) was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher who lived in Miletus,"Anaximander" in ''Chambers's Encyclopædia''. London: George Newnes, 1961, Vol. 1, p. 403. a city of Ionia (in moder ...

, famous for his proto-

evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation ...

ary theory, disputed Thales' ideas and proposed that rather than water, a substance called ''

apeiron

''Apeiron'' (; ) is a Greek word meaning "(that which is) unlimited," "boundless", "infinite", or "indefinite" from ''a-'', "without" and ''peirar'', "end, limit", "boundary", the Ionic Greek form of ''peras'', "end, limit, boundary".

Origin ...

'' was the building block of all matter. Around 500 BCE,

Heraclitus

Heraclitus of Ephesus (; grc-gre, Ἡράκλειτος , "Glory of Hera"; ) was an ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from the city of Ephesus, which was then part of the Persian Empire.

Little is known of Heraclitus's life. He wrote ...

proposed that the only basic law governing the

Universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. Acc ...

was the principle of change and that nothing remains in the same state indefinitely. This observation made him one of the first scholars in ancient physics to address the role of

time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

in the universe, a key and sometimes contentious concept in modern and present-day physics.

During the

classical period in Greece (6th, 5th and 4th centuries BCE) and in

Hellenistic times,

natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior throu ...

slowly developed into an exciting and contentious field of study.

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

( el, Ἀριστοτέλης, ''Aristotélēs'') (384 – 322 BCE), a student of

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

, promoted the concept that observation of physical phenomena could ultimately lead to the discovery of the natural laws governing them. Aristotle's writings cover physics,

metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

,

poetry

Poetry (derived from the Greek ''poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings i ...

,

theater

Theatre or theater is a collaborative form of performing art that uses live performers, usually actor, actors or actresses, to present the experience of a real or imagined event before a live audience in a specific place, often a stage. The p ...

,

music

Music is generally defined as the art of arranging sound to create some combination of form, harmony, melody, rhythm or otherwise expressive content. Exact definitions of music vary considerably around the world, though it is an aspect ...

,

logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premises ...

,

rhetoric

Rhetoric () is the art of persuasion, which along with grammar and logic (or dialectic), is one of the three ancient arts of discourse. Rhetoric aims to study the techniques writers or speakers utilize to inform, persuade, or motivate parti ...

,

linguistics

Linguistics is the scientific study of human language. It is called a scientific study because it entails a comprehensive, systematic, objective, and precise analysis of all aspects of language, particularly its nature and structure. Linguis ...

,

politics

Politics (from , ) is the set of activities that are associated with making decisions in groups, or other forms of power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. The branch of social science that studies ...

,

government

A government is the system or group of people governing an organized community, generally a state.

In the case of its broad associative definition, government normally consists of legislature, executive, and judiciary. Government is a ...

,

ethics

Ethics or moral philosophy is a branch of philosophy that "involves systematizing, defending, and recommending concepts of right and wrong behavior".''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy'' The field of ethics, along with aesthetics, concerns m ...

,

biology

Biology is the scientific study of life. It is a natural science with a broad scope but has several unifying themes that tie it together as a single, coherent field. For instance, all organisms are made up of cells that process hereditary i ...

and

zoology

Zoology ()The pronunciation of zoology as is usually regarded as nonstandard, though it is not uncommon. is the branch of biology that studies the Animal, animal kingdom, including the anatomy, structure, embryology, evolution, Biological clas ...

. He wrote the first work which refers to that line of study as "Physics" – in the 4th century BCE, Aristotle founded the system known as

Aristotelian physics

Aristotelian physics is the form of natural science described in the works of the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BC). In his work ''Physics'', Aristotle intended to establish general principles of change that govern all natural bodies, b ...

. He attempted to explain ideas such as

motion

In physics, motion is the phenomenon in which an object changes its position with respect to time. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed and frame of reference to an observer and mea ...

(and

gravity

In physics, gravity () is a fundamental interaction which causes mutual attraction between all things with mass or energy. Gravity is, by far, the weakest of the four fundamental interactions, approximately 1038 times weaker than the stro ...

) with the theory of

four elements

Classical elements typically refer to earth, water, air, fire, and (later) aether which were proposed to explain the nature and complexity of all matter in terms of simpler substances. Ancient cultures in Greece, Tibet, and India had simi ...

. Aristotle believed that all matter was made up of aether, or some combination of four elements: earth, water, air, and fire. According to Aristotle, these four terrestrial elements are capable of inter-transformation and move toward their natural place, so a stone falls downward toward the center of the cosmos, but flames rise upward toward the

circumference

In geometry, the circumference (from Latin ''circumferens'', meaning "carrying around") is the perimeter of a circle or ellipse. That is, the circumference would be the arc length of the circle, as if it were opened up and straightened out to ...

. Eventually,

Aristotelian physics

Aristotelian physics is the form of natural science described in the works of the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BC). In his work ''Physics'', Aristotle intended to establish general principles of change that govern all natural bodies, b ...

became enormously popular for many centuries in Europe, informing the scientific and scholastic developments of the

Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

. It remained the mainstream scientific paradigm in Europe until the time of

Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He was ...

and

Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a "natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the grea ...

.

Early in Classical Greece, knowledge that the Earth is

spherical

A sphere () is a geometrical object that is a three-dimensional analogue to a two-dimensional circle. A sphere is the set of points that are all at the same distance from a given point in three-dimensional space.. That given point is the ce ...

("round") was common. Around 240 BCE, as the result of

a seminal experiment,

Eratosthenes

Eratosthenes of Cyrene (; grc-gre, Ἐρατοσθένης ; – ) was a Greek polymath: a mathematician, geographer, poet, astronomer, and music theorist. He was a man of learning, becoming the chief librarian at the Library of Alexandria ...

(276–194 BCE) accurately estimated its circumference. In contrast to Aristotle's geocentric views,

Aristarchus of Samos

Aristarchus of Samos (; grc-gre, Ἀρίσταρχος ὁ Σάμιος, ''Aristarkhos ho Samios''; ) was an ancient Greek astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or ...

( el, Ἀρίσταρχος; c. 310 – c. 230 BCE) presented an explicit argument for a

heliocentric model

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth at ...

of the

Solar System

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar S ...

, i.e. for placing the

Sun

The Sun is the star at the center of the Solar System. It is a nearly perfect ball of hot plasma, heated to incandescence by nuclear fusion reactions in its core. The Sun radiates this energy mainly as light, ultraviolet, and infrared radi ...

, not the

Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surfa ...

, at its centre.

Seleucus of Seleucia

Seleucus of Seleucia ( el, Σέλευκος ''Seleukos''; born c. 190 BC; fl. c. 150 BC) was a Hellenistic astronomer and philosopher. Coming from Seleucia on the Tigris, Mesopotamia, the capital of the Seleucid Empire, or, alternatively, Seleuk ...

, a follower of Aristarchus' heliocentric theory, stated that

the Earth rotated around its own axis, which, in turn,

revolved around the Sun. Though the arguments he used were lost,

Plutarch

Plutarch (; grc-gre, Πλούταρχος, ''Ploútarchos''; ; – after AD 119) was a Greek Middle Platonist philosopher, historian, biographer, essayist, and priest at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. He is known primarily for his ''P ...

stated that Seleucus was the first to prove the heliocentric system through reasoning.

In the 3rd century BCE, the

Greek mathematician Archimedes of Syracuse

Archimedes of Syracuse (;; ) was a Greek mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor from the ancient city of Syracuse in Sicily. Although few details of his life are known, he is regarded as one of the leading scientists ...

( el,

Ἀρχιμήδης (287–212 BCE) – generally considered to be the greatest mathematician of antiquity and one of the greatest of all time – laid the foundations of

hydrostatics

Fluid statics or hydrostatics is the branch of fluid mechanics that studies the condition of the equilibrium of a floating body and submerged body " fluids at hydrostatic equilibrium and the pressure in a fluid, or exerted by a fluid, on an imm ...

,

statics

Statics is the branch of classical mechanics that is concerned with the analysis of force and torque (also called moment) acting on physical systems that do not experience an acceleration (''a''=0), but rather, are in static equilibrium with ...

and calculated the underlying mathematics of the

lever

A lever is a simple machine consisting of a beam or rigid rod pivoted at a fixed hinge, or ''fulcrum''. A lever is a rigid body capable of rotating on a point on itself. On the basis of the locations of fulcrum, load and effort, the lever is div ...

. A leading scientist of classical antiquity, Archimedes also developed elaborate systems of pulleys to move large objects with a minimum of effort. The

Archimedes' screw

The Archimedes screw, also known as the Archimedean screw, hydrodynamic screw, water screw or Egyptian screw, is one of the earliest hydraulic machines. Using Archimedes screws as water pumps (Archimedes screw pump (ASP) or screw pump) dates back ...

underpins modern hydroengineering, and his machines of war helped to hold back the armies of Rome in the

First Punic War

The First Punic War (264–241 BC) was the first of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the early 3rd century BC. For 23 years, in the longest continuous conflict and grea ...

. Archimedes even tore apart the arguments of Aristotle and his metaphysics, pointing out that it was impossible to separate mathematics and nature and proved it by converting mathematical theories into practical inventions. Furthermore, in his work ''

On Floating Bodies

''On Floating Bodies'' ( el, Περὶ τῶν ἐπιπλεόντων σωμάτων) is a Greek-language work consisting of two books written by Archimedes of Syracuse (287 – c. 212 BC), one of the most important mathematicians, physicis ...

'', around 250 BCE, Archimedes developed the law of

buoyancy

Buoyancy (), or upthrust, is an upward force exerted by a fluid that opposes the weight of a partially or fully immersed object. In a column of fluid, pressure increases with depth as a result of the weight of the overlying fluid. Thus the p ...

, also known as

Archimedes' principle

Archimedes' principle (also spelled Archimedes's principle) states that the upward buoyant force that is exerted on a body immersed in a fluid, whether fully or partially, is equal to the weight of the fluid that the body displaces. Archimede ...

. In mathematics, Archimedes used the method of exhaustion to calculate the area under the arc of a

parabola

In mathematics, a parabola is a plane curve which is mirror-symmetrical and is approximately U-shaped. It fits several superficially different mathematical descriptions, which can all be proved to define exactly the same curves.

One descript ...

with the summation of an infinite series, and gave a remarkably accurate approximation of

pi. He also defined the

spiral bearing his name, formulae for the

volume

Volume is a measure of occupied three-dimensional space. It is often quantified numerically using SI derived units (such as the cubic metre and litre) or by various imperial or US customary units (such as the gallon, quart, cubic inch). The de ...

s of surfaces of revolution and an ingenious system for expressing very large numbers. He also developed the principles of equilibrium states and

centers of gravity, ideas that would influence the well known scholars, Galileo, and Newton.

Hipparchus

Hipparchus (; el, Ἵππαρχος, ''Hipparkhos''; BC) was a Greek astronomer, geographer, and mathematician. He is considered the founder of trigonometry, but is most famous for his incidental discovery of the precession of the equi ...

(190–120 BCE), focusing on astronomy and mathematics, used sophisticated geometrical techniques to map the motion of the stars and

planet

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a you ...

s, even predicting the times that

Solar eclipse

A solar eclipse occurs when the Moon passes between Earth and the Sun, thereby obscuring the view of the Sun from a small part of the Earth, totally or partially. Such an alignment occurs during an eclipse season, approximately every six month ...

s would happen. He added calculations of the distance of the Sun and Moon from the Earth, based upon his improvements to the observational instruments used at that time. Another of the most famous of the early physicists was

Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of importanc ...

(90–168 CE), one of the leading minds during the time of the

Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

. Ptolemy was the author of several scientific treatises, at least three of which were of continuing importance to later Islamic and European science. The first is the astronomical treatise now known as the ''

Almagest

The ''Almagest'' is a 2nd-century Greek-language mathematical and astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Claudius Ptolemy ( ). One of the most influential scientific texts in history, it canoni ...

'' (in Greek, Ἡ Μεγάλη Σύνταξις, "The Great Treatise", originally Μαθηματικὴ Σύνταξις, "Mathematical Treatise"). The second is the ''

Geography

Geography (from Greek: , ''geographia''. Combination of Greek words ‘Geo’ (The Earth) and ‘Graphien’ (to describe), literally "earth description") is a field of science devoted to the study of the lands, features, inhabitants, and ...

'', which is a thorough discussion of the geographic knowledge of the

Greco-Roman world

The Greco-Roman civilization (; also Greco-Roman culture; spelled Graeco-Roman in the Commonwealth), as understood by modern scholars and writers, includes the geographical regions and countries that culturally—and so historically—were di ...

.

Much of the accumulated knowledge of the ancient world was lost. Even of the works of the better known thinkers, few fragments survived. Although he wrote at least fourteen books, almost nothing of Hipparchus' direct work survived. Of the 150 reputed

Aristotelian works, only 30 exist, and some of those are "little more than lecture notes".

India and China

Important physical and mathematical traditions also existed in

ancient Chinese and

Indian sciences.

In

Indian philosophy

Indian philosophy refers to philosophical traditions of the Indian subcontinent. A traditional Hindu classification divides āstika and nāstika schools of philosophy, depending on one of three alternate criteria: whether it believes the Veda ...

, Maharishi

Kanada Kanada may refer to:

*Kanada (philosopher), the Hindu sage who founded the philosophy of Vaisheshika

*Kanada (family of ragas), a group of ragas in Hindustani music

*Kanada (surname)

*Kanada Station, train station in Fukuoka, Japan

*Kannada, one of ...

was the first to systematically develop a theory of atomism around 200 BCE though some authors have allotted him an earlier era in the 6th century BCE. It was further elaborated by the

Buddhist atomists Dharmakirti

Dharmakīrti (fl. c. 6th or 7th century; Tibetan: ཆོས་ཀྱི་གྲགས་པ་; Wylie: ''chos kyi grags pa''), was an influential Indian Buddhist philosopher who worked at Nālandā.Tom Tillemans (2011)Dharmakirti Stanford ...

and

Dignāga

Dignāga (a.k.a. ''Diṅnāga'', c. 480 – c. 540 CE) was an Indian Buddhist scholar and one of the Buddhist founders of Indian logic (''hetu vidyā''). Dignāga's work laid the groundwork for the development of deductive logic in India and cr ...

during the 1st millennium CE.

Pakudha Kaccayana

was an Indian teacher and philosopher who lived around the 6th century BCE, contemporaneous with Mahavira and the Buddha. He was an atomist who believed in atomism which believed that everything is made of seven eternal elements – earth, wate ...

, a 6th-century BCE Indian philosopher and contemporary of

Gautama Buddha

Siddhartha Gautama, most commonly referred to as the Buddha, was a wandering ascetic and religious teacher who lived in South Asia during the 6th or 5th century BCE and founded Buddhism.

According to Buddhist tradition, he was born in Lu ...

, had also propounded ideas about the atomic constitution of the material world. These philosophers believed that other elements (except ether) were physically palpable and hence comprised minuscule particles of matter. The last minuscule particle of matter that could not be subdivided further was termed

Parmanu. These philosophers considered the atom to be indestructible and hence eternal. The Buddhists thought atoms to be minute objects unable to be seen to the naked eye that come into being and vanish in an instant. The

Vaisheshika

Vaisheshika or Vaiśeṣika ( sa, वैशेषिक) is one of the six schools of Indian philosophy (Vedic systems) from ancient India. In its early stages, the Vaiśeṣika was an independent philosophy with its own metaphysics, epistemolog ...

school of philosophers believed that an atom was a mere point in

space

Space is the boundless three-dimensional extent in which objects and events have relative position and direction. In classical physics, physical space is often conceived in three linear dimensions, although modern physicists usually consider ...

. It was also first to depict relations between motion and force applied. Indian theories about the atom are greatly abstract and enmeshed in philosophy as they were based on logic and not on personal experience or experimentation. In

Indian astronomy

Astronomy has long history in Indian subcontinent stretching from pre-historic to modern times. Some of the earliest roots of Indian astronomy can be dated to the period of Indus Valley civilisation or earlier. Astronomy later developed as a dis ...

,

Aryabhata

Aryabhata (ISO: ) or Aryabhata I (476–550 CE) was an Indian mathematician and astronomer of the classical age of Indian mathematics and Indian astronomy. He flourished in the Gupta Era and produced works such as the ''Aryabhatiya'' (which ...

's ''

Aryabhatiya

''Aryabhatiya'' (IAST: ') or ''Aryabhatiyam'' ('), a Sanskrit astronomical treatise, is the ''magnum opus'' and only known surviving work of the 5th century Indian mathematician Aryabhata. Philosopher of astronomy Roger Billard estimates that th ...

'' (499 CE) proposed the

Earth's rotation

Earth's rotation or Earth's spin is the rotation of planet Earth around its own Rotation around a fixed axis, axis, as well as changes in the orientation (geometry), orientation of the rotation axis in space. Earth rotates eastward, in retrograd ...

, while

Nilakantha Somayaji

Keļallur Nilakantha Somayaji (14 June 1444 – 1544), also referred to as Keļallur Comatiri, was a major mathematician and astronomer of the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics. One of his most influential works was the comprehens ...

(1444–1544) of the

Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics

The Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics or the Kerala school was a school of Indian mathematics, mathematics and Indian astronomy, astronomy founded by Madhava of Sangamagrama in Kingdom of Tanur, Tirur, Malappuram district, Malappuram, K ...

proposed a semi-heliocentric model resembling the

Tychonic system

The Tychonic system (or Tychonian system) is a model of the Universe published by Tycho Brahe in the late 16th century, which combines what he saw as the mathematical benefits of the Copernican system with the philosophical and "physical" bene ...

.

The study of

magnetism

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that are mediated by a magnetic field, which refers to the capacity to induce attractive and repulsive phenomena in other entities. Electric currents and the magnetic moments of elementary particles ...

in

Ancient China

The earliest known written records of the history of China date from as early as 1250 BC, from the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BC), during the reign of king Wu Ding. Ancient historical texts such as the '' Book of Documents'' (early chapte ...

dates back to the 4th century BCE. (in the ''Book of the Devil Valley Master''), A main contributor to this field was

Shen Kuo

Shen Kuo (; 1031–1095) or Shen Gua, courtesy name Cunzhong (存中) and pseudonym Mengqi (now usually given as Mengxi) Weng (夢溪翁),Yao (2003), 544. was a Chinese polymathic scientist and statesman of the Song dynasty (960–1279). Shen wa ...

(1031–1095), a

polymath

A polymath ( el, πολυμαθής, , "having learned much"; la, homo universalis, "universal human") is an individual whose knowledge spans a substantial number of subjects, known to draw on complex bodies of knowledge to solve specific pro ...

and statesman who was the first to describe the

magnetic-needle compass used for navigation, as well as establishing the concept of

true north

True north (also called geodetic north or geographic north) is the direction along Earth's surface towards the geographic North Pole or True North Pole.

Geodetic north differs from ''magnetic'' north (the direction a compass points toward the ...

. In optics, Shen Kuo independently developed a

camera obscura

A camera obscura (; ) is a darkened room with a aperture, small hole or lens at one side through which an image is 3D projection, projected onto a wall or table opposite the hole.

''Camera obscura'' can also refer to analogous constructions su ...

.

Joseph Needham

Noel Joseph Terence Montgomery Needham (; 9 December 1900 – 24 March 1995) was a British biochemist, historian of science and sinologist known for his scientific research and writing on the history of Chinese science and technology, in ...

, Volume 4, Part 1, 98.

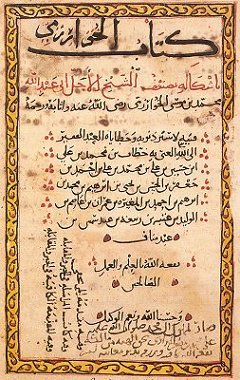

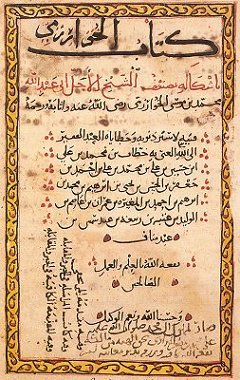

Islamic world

In the 7th to 15th centuries, scientific progress occurred in the Muslim world. Many classic works in

India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

n,

Assyria

Assyria (Neo-Assyrian cuneiform: , romanized: ''māt Aššur''; syc, ܐܬܘܪ, ʾāthor) was a major ancient Mesopotamian civilization which existed as a city-state at times controlling regional territories in the indigenous lands of the A ...

n,

Sassanian (Persian) and

Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

, including the works of

Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatetic school of phil ...

, were translated into

Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic languages, Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C ...

.

Important contributions were made by

Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the prin ...

(965–1040), an

Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

scientist, considered to be a founder of modern

optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultraviole ...

. Ptolemy and Aristotle theorised that light either shone from the eye to illuminate objects or that "forms" emanated from objects themselves, whereas al-Haytham (known by the Latin name "Alhazen") suggested that light travels to the eye in rays from different points on an object. The works of Ibn al-Haytham and

Abū Rayhān Bīrūnī

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of Co ...

(973–1050), a Persian scientist, eventually passed on to Western Europe where they were studied by scholars such as

Roger Bacon

Roger Bacon (; la, Rogerus or ', also '' Rogerus''; ), also known by the scholastic accolade ''Doctor Mirabilis'', was a medieval English philosopher and Franciscan friar who placed considerable emphasis on the study of nature through empiri ...

and

Witelo

Vitello ( pl, Witelon; german: Witelo; – 1280/1314) was a friar, theologian, natural philosopher and an important figure in the history of philosophy in Poland.

Name

Vitello's name varies with some sources. In earlier publications he was quo ...

.

Ibn al-Haytham and Biruni were early proponents of the

scientific method

The scientific method is an empirical method for acquiring knowledge that has characterized the development of science since at least the 17th century (with notable practitioners in previous centuries; see the article history of scientific m ...

. Ibn al-Haytham is considered to be by some the "father of the modern scientific method" due to his emphasis on experimental data and

reproducibility

Reproducibility, also known as replicability and repeatability, is a major principle underpinning the scientific method. For the findings of a study to be reproducible means that results obtained by an experiment or an observational study or in a ...

of its results.

The earliest methodical approach to

experiment

An experiment is a procedure carried out to support or refute a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy or likelihood of something previously untried. Experiments provide insight into Causality, cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome oc ...

s in the modern sense is visible in the works of Ibn al-Haytham, who introduced an inductive-experimental method for achieving results. Bīrūnī introduced early scientific methods for several different fields of

inquiry

An inquiry (also spelled as enquiry in British English) is any process that has the aim of augmenting knowledge, resolving doubt, or solving a problem. A theory of inquiry is an account of the various types of inquiry and a treatment of the ...

during the 1020s and 1030s,

including an early experimental method for

mechanics

Mechanics (from Ancient Greek: μηχανική, ''mēkhanikḗ'', "of machines") is the area of mathematics and physics concerned with the relationships between force, matter, and motion among physical objects. Forces applied to objects r ...

.

[Mariam Rozhanskaya and I. S. Levinova (1996), "Statics", p. 642, in : ] Biruni's methodology resembled the modern scientific method, particularly in his emphasis on repeated experimentation.

Ibn Sīnā

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islamic ...

(980–1037), known as "Avicenna", was a polymath from

Bukhara

Bukhara (Uzbek language, Uzbek: /, ; tg, Бухоро, ) is the List of cities in Uzbekistan, seventh-largest city in Uzbekistan, with a population of 280,187 , and the capital of Bukhara Region.

People have inhabited the region around Bukhara ...

(in present-day

Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan (, ; uz, Ozbekiston, italic=yes / , ; russian: Узбекистан), officially the Republic of Uzbekistan ( uz, Ozbekiston Respublikasi, italic=yes / ; russian: Республика Узбекистан), is a doubly landlocked cou ...

) responsible for important contributions to physics, optics, philosophy and

medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pract ...

. He published his theory of

motion

In physics, motion is the phenomenon in which an object changes its position with respect to time. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed and frame of reference to an observer and mea ...

in ''

Book of Healing'' (1020), where he argued that an impetus is imparted to a projectile by the thrower, and believed that it was a temporary virtue that would decline even in a vacuum. He viewed it as persistent, requiring external forces such as

air resistance

In fluid dynamics, drag (sometimes called air resistance, a type of friction, or fluid resistance, another type of friction or fluid friction) is a force acting opposite to the relative motion of any object moving with respect to a surrounding flu ...

to dissipate it.

Ibn Sina made a distinction between 'force' and 'inclination' (called "mayl"), and argued that an object gained mayl when the object is in opposition to its natural motion. He concluded that continuation of motion is attributed to the inclination that is transferred to the object, and that object will be in motion until the mayl is spent. He also claimed that projectile in a vacuum would not stop unless it is acted upon. This conception of motion is consistent with

Newton's first law of motion

Newton's laws of motion are three basic laws of classical mechanics that describe the relationship between the motion of an object and the forces acting on it. These laws can be paraphrased as follows:

# A body remains at rest, or in motion ...

,

inertia

Inertia is the idea that an object will continue its current motion until some force causes its speed or direction to change. The term is properly understood as shorthand for "the principle of inertia" as described by Newton in his first law ...

, which states that an object in motion will stay in motion unless it is acted on by an external force.

This idea which dissented from the Aristotelian view was later described as "

impetus" by

John Buridan

Jean Buridan (; Latin: ''Johannes Buridanus''; – ) was an influential 14th-century French philosopher.

Buridan was a teacher in the faculty of arts at the University of Paris for his entire career who focused in particular on logic and the wo ...

, who was influenced by Ibn Sina's ''Book of Healing''.

[Sayili, Aydin. "Ibn Sina and Buridan on the Motion the Projectile". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences vol. 500(1). p.477-482.]

Hibat Allah Abu'l-Barakat al-Baghdaadi

Hibat Allah Abu'l-Barakat al-Baghdaadi (c. 1080-1165) adopted and modified Ibn Sina's theory on

projectile motion

Projectile motion is a form of motion experienced by an object or particle (a projectile) that is projected in a gravitational field, such as from Earth's surface, and moves along a curved path under the action of gravity only. In the particul ...

. In his ''Kitab al-Mu'tabar'', Abu'l-Barakat stated that the mover imparts a violent inclination (''mayl qasri'') on the moved and that this diminishes as the moving object distances itself from the mover.

He also proposed an explanation of the

acceleration

In mechanics, acceleration is the rate of change of the velocity of an object with respect to time. Accelerations are vector quantities (in that they have magnitude and direction). The orientation of an object's acceleration is given by the ...

of falling bodies by the accumulation of successive increments of

power

Power most often refers to:

* Power (physics), meaning "rate of doing work"

** Engine power, the power put out by an engine

** Electric power

* Power (social and political), the ability to influence people or events

** Abusive power

Power may a ...

with successive increments of

velocity

Velocity is the directional speed of an object in motion as an indication of its rate of change in position as observed from a particular frame of reference and as measured by a particular standard of time (e.g. northbound). Velocity is a ...

. According to

Shlomo Pines

Shlomo Pines (; ; August 5, 1908 in Charenton-le-Pont – January 9, 1990 in Jerusalem) was an Israeli scholar of Jewish and Islamic philosophy, best known for his English translation of Maimonides' ''Guide of the Perplexed''.

Biography

Pines wa ...

, al-Baghdaadi's theory of motion was "the oldest negation of Aristotle's fundamental dynamic law

amely, that a constant force produces a uniform motion nd is thus ananticipation in a vague fashion of the fundamental law of

classical mechanics

Classical mechanics is a physical theory describing the motion of macroscopic objects, from projectiles to parts of machinery, and astronomical objects, such as spacecraft, planets, stars, and galaxies. For objects governed by classical ...

amely, that a force applied continuously produces acceleration" Jean Buridan and

Albert of Saxony

en, Frederick Augustus Albert Anthony Ferdinand Joseph Charles Maria Baptist Nepomuk William Xavier George Fidelis

, image = Albert of Saxony by Nicola Perscheid c1900.jpg

, image_size =

, caption = Photograph by Nicola Persch ...

later referred to Abu'l-Barakat in explaining that the acceleration of a falling body is a result of its increasing impetus.

Ibn Bajjah

Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Yaḥyà ibn aṣ-Ṣā’igh at-Tūjībī ibn Bājja ( ar, أبو بكر محمد بن يحيى بن الصائغ التجيبي بن باجة), best known by his Latinised name Avempace (; – 1138), was an A ...

(c. 1085–1138), known as "Avempace" in Europe, proposed that for every force there is always a

reaction

Reaction may refer to a process or to a response to an action, event, or exposure:

Physics and chemistry

*Chemical reaction

*Nuclear reaction

*Reaction (physics), as defined by Newton's third law

*Chain reaction (disambiguation).

Biology and me ...

force. Ibn Bajjah was a critic of Ptolemy and he worked on creating a new theory of velocity to replace the one theorized by Aristotle. Two future philosophers supported the theories Avempace created, known as Avempacean dynamics. These philosophers were

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wi ...

, a Catholic priest, and

John Duns Scotus

John Duns Scotus ( – 8 November 1308), commonly called Duns Scotus ( ; ; "Duns the Scot"), was a Scottish Catholic priest and Franciscan friar, university professor, philosopher, and theologian. He is one of the four most important ...

.

Galileo

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He was ...

went on to adopt Avempace's formula "that the velocity of a given object is the difference of the motive power of that object and the resistance of the medium of motion".

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi

Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Tūsī ( fa, محمد ابن محمد ابن حسن طوسی 18 February 1201 – 26 June 1274), better known as Nasir al-Din al-Tusi ( fa, نصیر الدین طوسی, links=no; or simply Tusi in the West ...

(1201–1274), a Persian astronomer and mathematician who died in Baghdad introduced the

Tusi couple

The Tusi couple is a mathematical device in which a small circle rotates inside a larger circle twice the diameter of the smaller circle. Rotations of the circles cause a point on the circumference of the smaller circle to oscillate back and fort ...

. Copernicus later drew heavily on the work of al-Din al-Tusi and his students, but without acknowledgment.

Medieval Europe

Awareness of ancient works re-entered the West through

translations from Arabic to Latin. Their re-introduction, combined with

Judeo-Islamic theological commentaries, had a great influence on

Medieval philosophers such as

Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wi ...

.

Scholastic European scholars, who sought to reconcile the philosophy of the ancient classical philosophers with

Christian theology

Christian theology is the theology of Christianity, Christian belief and practice. Such study concentrates primarily upon the texts of the Old Testament and of the New Testament, as well as on Christian tradition. Christian theology, theologian ...

, proclaimed Aristotle the greatest thinker of the ancient world. In cases where they didn't directly contradict the Bible, Aristotelian physics became the foundation for the physical explanations of the European Churches. Quantification became a core element of medieval physics.

Based on Aristotelian physics, Scholastic physics described things as moving according to their essential nature. Celestial objects were described as moving in circles, because perfect circular motion was considered an innate property of objects that existed in the uncorrupted realm of the

celestial spheres

The celestial spheres, or celestial orbs, were the fundamental entities of the cosmology, cosmological models developed by Plato, Eudoxus of Cnidus, Eudoxus, Aristotle, Ptolemy, Copernicus, and others. In these celestial models, the diurnal m ...

. The

theory of impetus

The theory of impetus was an auxiliary or secondary theory of Aristotelian dynamics, put forth initially to explain projectile motion against gravity. It was introduced by John Philoponus in the 6th century, and elaborated by Nur ad-Din al-Bitruj ...

, the ancestor to the concepts of

inertia

Inertia is the idea that an object will continue its current motion until some force causes its speed or direction to change. The term is properly understood as shorthand for "the principle of inertia" as described by Newton in his first law ...

and

momentum

In Newtonian mechanics, momentum (more specifically linear momentum or translational momentum) is the product of the mass and velocity of an object. It is a vector quantity, possessing a magnitude and a direction. If is an object's mass an ...

, was developed along similar lines by

medieval philosophers such as

John Philoponus

John Philoponus (Greek: ; ; c. 490 – c. 570), also known as John the Grammarian or John of Alexandria, was a Byzantine Greek philologist, Aristotelian commentator, Christian theologian and an author of a considerable number of philosophical tre ...

and

Jean Buridan

Jean Buridan (; Latin: ''Johannes Buridanus''; – ) was an influential 14th-century French people, French Philosophy, philosopher.

Buridan was a teacher in the Faculty (division)#Faculty of Art, faculty of arts at the University of Paris for hi ...

. Motions below the lunar sphere were seen as imperfect, and thus could not be expected to exhibit consistent motion. More idealized motion in the "sublunary" realm could only be achieved through

artifice

''Artifice'' was a nonprofit literary magazine based in Chicago, Illinois, that existed between 2009 and 2017.

History and profile

''Artifice'' was started in 2009. It was co-founded by Rebekah Silverman, who served as Managing Editor, and James ...

, and prior to the 17th century, many did not view artificial experiments as a valid means of learning about the natural world. Physical explanations in the sublunary realm revolved around tendencies. Stones contained the element earth, and earthly objects tended to move in a straight line toward the centre of the earth (and the universe in the Aristotelian geocentric view) unless otherwise prevented from doing so.

Scientific revolution

During the 16th and 17th centuries, a large advancement of scientific progress known as the

Scientific revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of modern science during the early modern period, when developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology (including human anatomy) and chemistry transfo ...

took place in Europe. Dissatisfaction with older philosophical approaches had begun earlier and had produced other changes in society, such as the

Protestant Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

, but the revolution in science began when

natural philosophers

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wor ...

began to mount a sustained attack on the

Scholastic philosophical programme and supposed that mathematical descriptive schemes adopted from such fields as mechanics and astronomy could actually yield universally valid characterizations of motion and other concepts.

Nicolaus Copernicus

A breakthrough in

astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

was made by Polish astronomer

Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic Church, Catholic cano ...

(1473–1543) when, in 1543, he gave strong arguments for the

heliocentric model

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth at ...

of the

Solar System

The Solar SystemCapitalization of the name varies. The International Astronomical Union, the authoritative body regarding astronomical nomenclature, specifies capitalizing the names of all individual astronomical objects but uses mixed "Solar S ...

, ostensibly as a means to render tables charting planetary motion more accurate and to simplify their production. In heliocentric models of the Solar system, the Earth orbits the Sun along with other bodies in

Earth's galaxy

A galaxy is a system of stars, stellar remnants, interstellar gas, dust, dark matter, bound together by gravity. The word is derived from the Greek ' (), literally 'milky', a reference to the Milky Way galaxy that contains the Solar System. ...

, a contradiction according to the Greek-Egyptian astronomer Ptolemy (2nd century CE; see above),

whose system placed the Earth at the center of the Universe and had been accepted for over 1,400 years. The Greek astronomer

Aristarchus of Samos

Aristarchus of Samos (; grc-gre, Ἀρίσταρχος ὁ Σάμιος, ''Aristarkhos ho Samios''; ) was an ancient Greek astronomer

An astronomer is a scientist in the field of astronomy who focuses their studies on a specific question or ...

(c.310 – c.230 BCE) had suggested that the Earth revolves around the Sun, but Copernicus' reasoning led to lasting general acceptance of this "revolutionary" idea. Copernicus' book presenting the theory (''

De revolutionibus orbium coelestium

''De revolutionibus orbium coelestium'' (English translation: ''On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres'') is the seminal work on the heliocentric theory of the astronomer Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) of the Polish Renaissance. The book, ...

'', "On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres") was published just before his death in 1543 and, as it is now generally considered to mark the beginning of modern astronomy, is also considered to mark the beginning of the Scientific revolution. Copernicus' new perspective, along with the accurate observations made by

Tycho Brahe

Tycho Brahe ( ; born Tyge Ottesen Brahe; generally called Tycho (14 December 154624 October 1601) was a Danish astronomer, known for his comprehensive astronomical observations, generally considered to be the most accurate of his time. He was k ...

, enabled German astronomer

Johannes Kepler

Johannes Kepler (; ; 27 December 1571 – 15 November 1630) was a German astronomer, mathematician, astrologer, natural philosopher and writer on music. He is a key figure in the 17th-century Scientific Revolution, best known for his laws ...

(1571–1630) to formulate

his laws regarding planetary motion that remain in use today.

Galileo Galilei

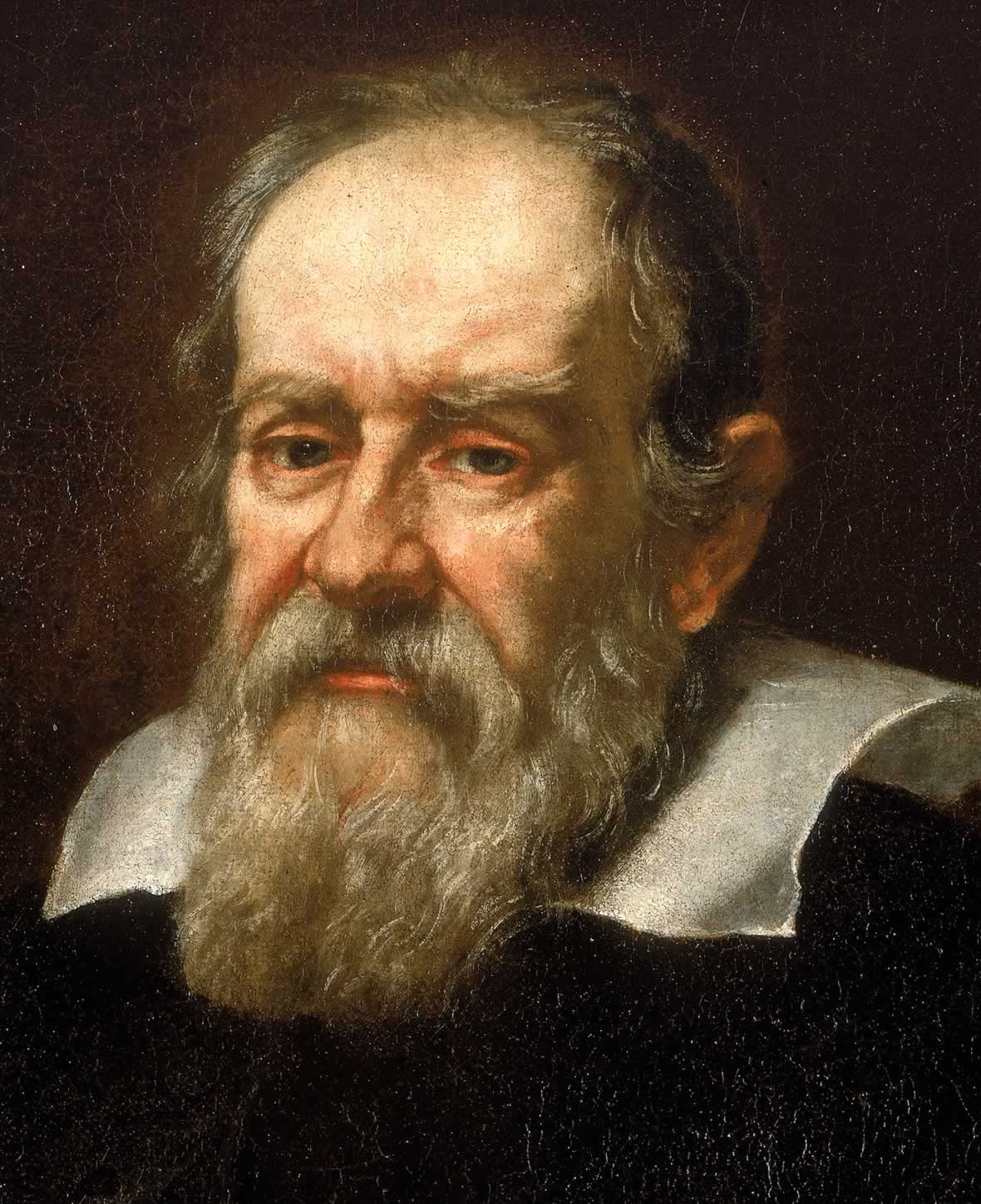

The Italian mathematician, astronomer, and physicist

Galileo Galilei

Galileo di Vincenzo Bonaiuti de' Galilei (15 February 1564 – 8 January 1642) was an Italian astronomer, physicist and engineer, sometimes described as a polymath. Commonly referred to as Galileo, his name was pronounced (, ). He was ...

(1564–1642) was famous for his support for Copernicanism, his astronomical discoveries, empirical experiments and his improvement of the telescope. As a mathematician, Galileo's role in the

university

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, t ...

culture of his era was subordinated to the three major topics of study:

law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

,

medicine

Medicine is the science and practice of caring for a patient, managing the diagnosis, prognosis, prevention, treatment, palliation of their injury or disease, and promoting their health. Medicine encompasses a variety of health care pract ...

, and

theology

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the ...

(which was closely allied to philosophy). Galileo, however, felt that the descriptive content of the technical disciplines warranted philosophical interest, particularly because mathematical analysis of astronomical observations – notably, Copernicus' analysis of the

relative motions of the Sun, Earth, Moon, and planets – indicated that philosophers' statements about the nature of the universe could be shown to be in error. Galileo also performed mechanical experiments, insisting that motion itself – regardless of whether it was produced "naturally" or "artificially" (i.e. deliberately) – had universally consistent characteristics that could be described mathematically.

Galileo's early studies at the

University of Pisa

The University of Pisa ( it, Università di Pisa, UniPi), officially founded in 1343, is one of the oldest universities in Europe.

History

The Origins

The University of Pisa was officially founded in 1343, although various scholars place ...

were in medicine, but he was soon drawn to mathematics and physics. At 19, he discovered (and,

subsequently, verified) the

isochronal nature of the

pendulum

A pendulum is a weight suspended from a pivot so that it can swing freely. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate it back toward the ...

when, using his pulse, he timed the oscillations of a swinging lamp in

Pisa's cathedral and found that it remained the same for each swing regardless of the swing's

amplitude

The amplitude of a periodic variable is a measure of its change in a single period (such as time or spatial period). The amplitude of a non-periodic signal is its magnitude compared with a reference value. There are various definitions of amplit ...

. He soon became known through his invention of a

hydrostatic balance

In fluid mechanics, hydrostatic equilibrium (hydrostatic balance, hydrostasy) is the condition of a fluid or plastic solid at rest, which occurs when external forces, such as gravity, are balanced by a pressure-gradient force. In the planetary ...

and for his treatise on the

center of gravity

In physics, the center of mass of a distribution of mass in space (sometimes referred to as the balance point) is the unique point where the weight function, weighted relative position (vector), position of the distributed mass sums to zero. Thi ...

of solid bodies. While teaching at the University of Pisa (1589–92), he initiated his experiments concerning the laws of bodies in motion that brought results so contradictory to the accepted teachings of Aristotle that strong antagonism was aroused. He found that bodies do not fall with velocities

proportional to their weights. The famous story in which Galileo is said to have

dropped weights from the

Leaning Tower of Pisa

The Leaning Tower of Pisa ( it, torre pendente di Pisa), or simply, the Tower of Pisa (''torre di Pisa'' ), is the ''bell tower, campanile'', or freestanding bell tower, of Pisa Cathedral. It is known for its nearly four-degree lean, the result ...

is apocryphal, but he did find that the

path of a projectile is a

parabola

In mathematics, a parabola is a plane curve which is mirror-symmetrical and is approximately U-shaped. It fits several superficially different mathematical descriptions, which can all be proved to define exactly the same curves.

One descript ...

and is credited with conclusions that anticipated

Newton's laws of motion

Newton's laws of motion are three basic laws of classical mechanics that describe the relationship between the motion of an object and the forces acting on it. These laws can be paraphrased as follows:

# A body remains at rest, or in moti ...

(e.g. the notion of

inertia

Inertia is the idea that an object will continue its current motion until some force causes its speed or direction to change. The term is properly understood as shorthand for "the principle of inertia" as described by Newton in his first law ...

). Among these is what is now called

Galilean relativity

Galilean invariance or Galilean relativity states that the laws of motion are the same in all inertial frames of reference. Galileo Galilei first described this principle in 1632 in his '' Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'' using t ...

, the first precisely formulated statement about properties of space and time outside

three-dimensional geometry

In mathematics, solid geometry or stereometry is the traditional name for the geometry of three-dimensional, Euclidean spaces (i.e., 3D geometry).

Stereometry deals with the measurements of volumes of various solid figures (or 3D figures), inc ...

.

Galileo has been called the "father of modern

observational astronomy

Observational astronomy is a division of astronomy that is concerned with recording data about the observable universe, in contrast with theoretical astronomy, which is mainly concerned with calculating the measurable implications of physical m ...

", the "father of

modern physics

Modern physics is a branch of physics that developed in the early 20th century and onward or branches greatly influenced by early 20th century physics. Notable branches of modern physics include quantum mechanics, special relativity and general ...

",

the "father of science",

and "the father of

modern science

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient history, ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural science, natural, social science, social, and formal science, formal.

Sc ...

".

[ Finocchiaro (2007).] According to

Stephen Hawking, "Galileo, perhaps more than any other single person, was responsible for the birth of modern science." As religious orthodoxy decreed a

geocentric

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, an ...

or

Tychonic understanding of the Solar system, Galileo's support for

heliocentrism

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth at ...

provoked controversy and he was tried by the

Inquisition

The Inquisition was a group of institutions within the Catholic Church whose aim was to combat heresy, conducting trials of suspected heretics. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, ...

. Found "vehemently suspect of heresy", he was forced to recant and spent the rest of his life under house arrest.

The contributions that Galileo made to observational astronomy include the telescopic confirmation of the

phases of Venus

The phases of Venus are the variations of lighting seen on the planet's surface, similar to lunar phases. The first recorded observations of them are thought to have been telescopic observations by Galileo Galilei in 1610. Although the extreme cr ...

; his discovery, in 1609, of

Jupiter's four largest moons (subsequently given the collective name of the "

Galilean moons

The Galilean moons (), or Galilean satellites, are the four largest moons of Jupiter: Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. They were first seen by Galileo Galilei in December 1609 or January 1610, and recognized by him as satellites of Jupiter ...

"); and the observation and analysis of

sunspot

Sunspots are phenomena on the Sun's photosphere that appear as temporary spots that are darker than the surrounding areas. They are regions of reduced surface temperature caused by concentrations of magnetic flux that inhibit convection. Sun ...

s. Galileo also pursued applied science and technology, inventing, among other instruments, a military

compass

A compass is a device that shows the cardinal directions used for navigation and geographic orientation. It commonly consists of a magnetized needle or other element, such as a compass card or compass rose, which can pivot to align itself with ...

. His discovery of the Jovian moons

was published in 1610 and enabled him to obtain the position of mathematician and philosopher to the

Medici

The House of Medici ( , ) was an Italian banking family and political dynasty that first began to gather prominence under Cosimo de' Medici, in the Republic of Florence during the first half of the 15th century. The family originated in the Muge ...

court. As such, he was expected to engage in debates with philosophers in the Aristotelian tradition and received a large audience for his own publications such as the ''

Discourses and Mathematical Demonstrations Concerning Two New Sciences'' (published abroad following his arrest for the publication of ''

Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems

The ''Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems'' (''Dialogo sopra i due massimi sistemi del mondo'') is a 1632 Italian-language book by Galileo Galilei comparing the Copernican system with the traditional Ptolemaic system. It was tran ...

'') and ''

The Assayer

''The Assayer'' ( it, Il Saggiatore) was a book published in Rome by Galileo Galilei in October 1623 and is generally considered to be one of the pioneering works of the scientific method, first broaching the idea that the book of nature is to be ...

''. Galileo's interest in experimenting with and formulating mathematical descriptions of motion established experimentation as an integral part of natural philosophy. This tradition, combining with the non-mathematical emphasis on the collection of "experimental histories" by philosophical reformists such as

William Gilbert and

Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban (; 22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626), also known as Lord Verulam, was an English philosopher and statesman who served as Attorney General and Lord Chancellor of England. Bacon led the advancement of both ...

, drew a significant following in the years leading up to and following Galileo's death, including

Evangelista Torricelli

Evangelista Torricelli ( , also , ; 15 October 160825 October 1647) was an Italian physicist and mathematician, and a student of Galileo. He is best known for his invention of the barometer, but is also known for his advances in optics and work o ...

and the participants in the

Accademia del Cimento

The Accademia del Cimento (Academy of Experiment), an early scientific society, was founded in Florence in 1657 by students of Galileo, Giovanni Alfonso Borelli and Vincenzo Viviani and ceased to exist about a decade later. The foundation of Acade ...

in Italy;

Marin Mersenne

Marin Mersenne, OM (also known as Marinus Mersennus or ''le Père'' Mersenne; ; 8 September 1588 – 1 September 1648) was a French polymath whose works touched a wide variety of fields. He is perhaps best known today among mathematicians for ...

and

Blaise Pascal

Blaise Pascal ( , , ; ; 19 June 1623 – 19 August 1662) was a French mathematician, physicist, inventor, philosopher, and Catholic Church, Catholic writer.

He was a child prodigy who was educated by his father, a tax collector in Rouen. Pa ...

in France;

Christiaan Huygens

Christiaan Huygens, Lord of Zeelhem, ( , , ; also spelled Huyghens; la, Hugenius; 14 April 1629 – 8 July 1695) was a Dutch mathematician, physicist, engineer, astronomer, and inventor, who is regarded as one of the greatest scientists of ...

in the Netherlands; and

Robert Hooke

Robert Hooke FRS (; 18 July 16353 March 1703) was an English polymath active as a scientist, natural philosopher and architect, who is credited to be one of two scientists to discover microorganisms in 1665 using a compound microscope that ...

and

Robert Boyle

Robert Boyle (; 25 January 1627 – 31 December 1691) was an Anglo-Irish natural philosopher, chemist, physicist, alchemist and inventor. Boyle is largely regarded today as the first modern chemist, and therefore one of the founders of ...

in England.

René Descartes

The French philosopher

René Descartes

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Mathem ...

(1596–1650) was well-connected to, and influential within, the experimental philosophy networks of the day. Descartes had a more ambitious agenda, however, which was geared toward replacing the Scholastic philosophical tradition altogether. Questioning the reality interpreted through the senses, Descartes sought to re-establish philosophical explanatory schemes by reducing all perceived phenomena to being attributable to the motion of an invisible sea of "corpuscles". (Notably, he reserved human thought and

God

In monotheism, monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator deity, creator, and principal object of Faith#Religious views, faith.Richard Swinburne, Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Ted Honderich, Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Ox ...

from his scheme, holding these to be separate from the physical universe). In proposing this philosophical framework, Descartes supposed that different kinds of motion, such as that of planets versus that of terrestrial objects, were not fundamentally different, but were merely different manifestations of an endless chain of corpuscular motions obeying universal principles. Particularly influential were his explanations for circular astronomical motions in terms of the vortex motion of corpuscles in space (Descartes argued, in accord with the beliefs, if not the methods, of the Scholastics, that a

vacuum

A vacuum is a space devoid of matter. The word is derived from the Latin adjective ''vacuus'' for "vacant" or "void". An approximation to such vacuum is a region with a gaseous pressure much less than atmospheric pressure. Physicists often dis ...

could not exist), and his explanation of

gravity

In physics, gravity () is a fundamental interaction which causes mutual attraction between all things with mass or energy. Gravity is, by far, the weakest of the four fundamental interactions, approximately 1038 times weaker than the stro ...

in terms of corpuscles pushing objects downward.

Descartes, like Galileo, was convinced of the importance of mathematical explanation, and he and his followers were key figures in the development of mathematics and geometry in the 17th century. Cartesian mathematical descriptions of motion held that all mathematical formulations had to be justifiable in terms of direct physical action, a position held by

Huygens and the German philosopher

Gottfried Leibniz

Gottfried Wilhelm (von) Leibniz . ( – 14 November 1716) was a German polymath active as a mathematician, philosopher, scientist and diplomat. He is one of the most prominent figures in both the history of philosophy and the history of mathem ...

, who, while following in the Cartesian tradition, developed his own philosophical alternative to Scholasticism, which he outlined in his 1714 work, ''

The Monadology

The ''Monadology'' (french: La Monadologie, 1714) is one of Gottfried Leibniz's best known works of his later philosophy. It is a short text which presents, in some 90 paragraphs, a metaphysics of simple substances, or '' monads''.

Text

Dur ...

''. Descartes has been dubbed the 'Father of Modern Philosophy', and much subsequent

Western philosophy

Western philosophy encompasses the philosophical thought and work of the Western world. Historically, the term refers to the philosophical thinking of Western culture, beginning with the ancient Greek philosophy of the pre-Socratics. The word ' ...

is a response to his writings, which are studied closely to this day. In particular, his ''

Meditations on First Philosophy

''Meditations on First Philosophy, in which the existence of God and the immortality of the soul are demonstrated'' ( la, Meditationes de Prima Philosophia, in qua Dei existentia et animæ immortalitas demonstratur) is a philosophical treatise ...

'' continues to be a standard text at most university philosophy departments. Descartes' influence in mathematics is equally apparent; the

Cartesian coordinate system

A Cartesian coordinate system (, ) in a plane is a coordinate system that specifies each point uniquely by a pair of numerical coordinates, which are the signed distances to the point from two fixed perpendicular oriented lines, measured in t ...